For decades, football’s visual language lived in scrawled tags, club slogans and firm-related graffiti around stadiums and train stations – raw signals of territory, loyalty and rivalry. Today, that tradition has evolved. In the words and photographs of French photojournalist Guirec Munier, the streets reveal a different layer of the game: large-scale murals, portraits of icons, and politically charged artworks that turn neighbourhood walls into cultural landmarks. From working-class districts in the UK to vast cityscapes in North and West Africa, street art has become a powerful form of expression within popular culture, blending football, identity and community pride. This new wave of creativity does more than decorate urban space; it deepens the bond between clubs and the people who live around them. Murals humanise heroes, tell local stories, and give supporters a shared visual history – proof that football’s influence extends far beyond the pitch and into the everyday life of the streets.

“I’ve been a street art enthusiast for about twenty years, and its rather sudden emergence in the football sphere immediately caught my attention. In some cases, most notably at Anfield, murals have become the new statues. From Jürgen Klopp to Mohamed Salah, by way of the icons of previous decades, Liverpool FC cultivates its rich history on the walls of the terraced houses located within a 500-metre radius of the Reds’ home ground.

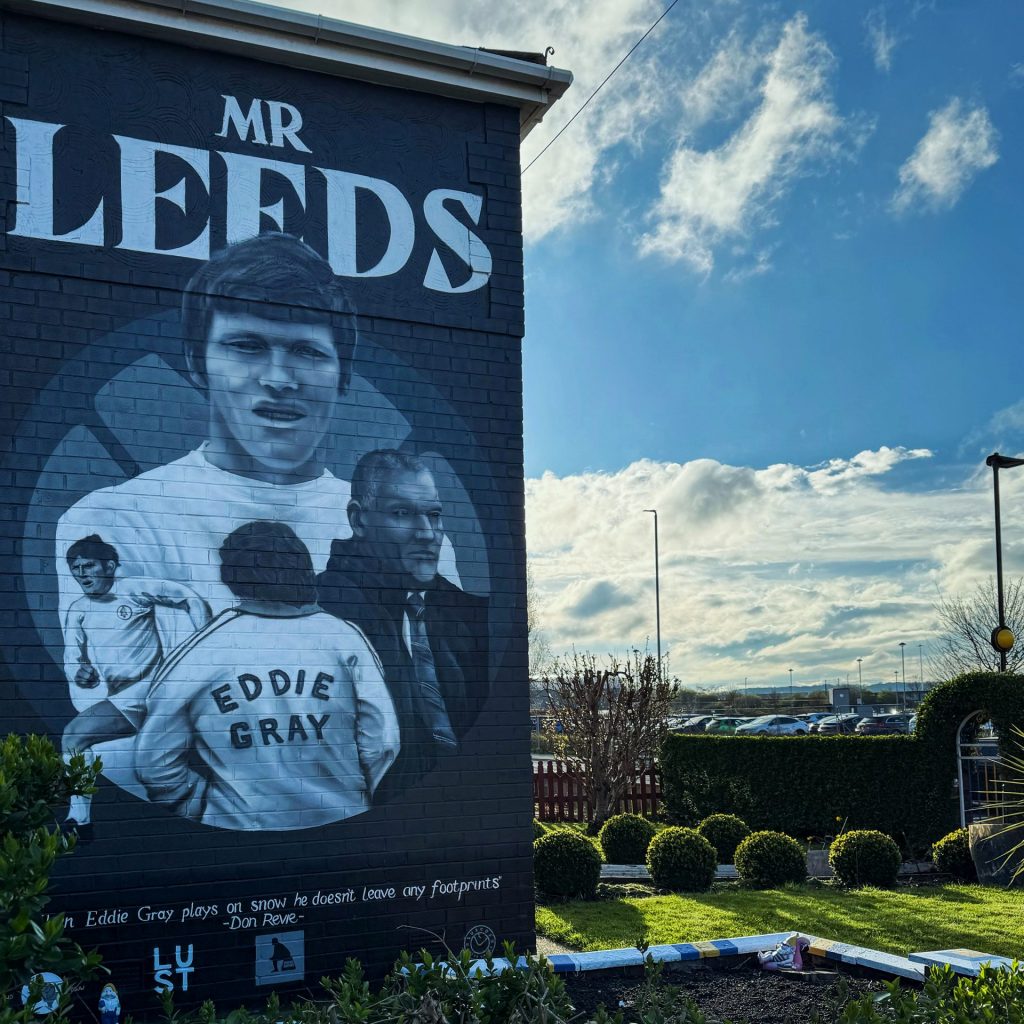

Also with the aim of symbolising the indelible mark left by an important figure in the history of a club and then a city, Nicolas Dixon, Tankpetrol, and Burley Banksy have elevated Marcelo Bielsa to the status of a Christ-like figure, a spiritual leader, and a pop culture hero in Leeds.

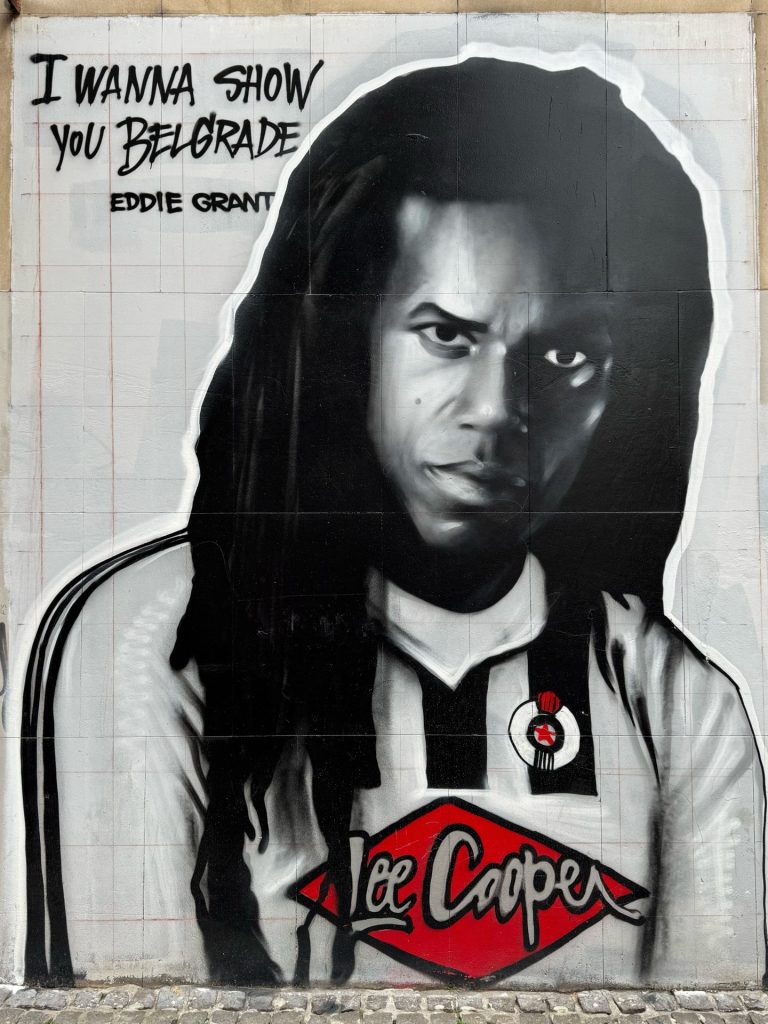

In another context, in cities with at least two top-level clubs, walls serve to mark territory in certain neighbourhoods loyal to a particular club. Belgrade perfectly embodies this situation. Dorćol is full of murals paying homage to important figures of Partizan Belgrade. Neimar, on the other hand, is teeming with references to Red Star Belgrade.

Protest-oriented and politically engaged, street art is also, and above all, a voice for political and social causes. Dalymount Park, the home of Bohs, is an open forum on the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, the reception of refugees, LGBTQ+ rights, the reunification of Ireland, and the protection of the working class.

Last but not least, street art does not play a central role in the European ultra movement, but it is strongly present in North Africa, particularly in Casablanca. However, groups such as the Roazhon Celtic Kop in Rennes (creator of the Banditi, later adopted by Curva Sud Milano), Delije in Belgrade, and several groups from the Secondo Anello Verde (Brianza Alcoolica, Squilibrati, Boys-San, etc.) in Milan have mastered this art form. Located in the immediate vicinity of stadiums or integrated into the city, street art has its place in the football subculture – long may it last!”

-

Campo da Calcio – Naples£50.00 – £75.00Price range: £50.00 through £75.00

Campo da Calcio – Naples£50.00 – £75.00Price range: £50.00 through £75.00 -

Colombia Fiesta, Italia 90£100.00 – £150.00Price range: £100.00 through £150.00

Colombia Fiesta, Italia 90£100.00 – £150.00Price range: £100.00 through £150.00 -

The Twelfth Man, USA 94£100.00 – £150.00Price range: £100.00 through £150.00

The Twelfth Man, USA 94£100.00 – £150.00Price range: £100.00 through £150.00