For Duncan Quinton, Old Trafford has been the backdrop to a lifetime of memories as a Manchester United supporter. Growing up in the Rossendale valleys before moving to Shropshire, Duncan’s obsession with United began as a teenager in the late 1980s. Alongside friends who had never seen the ground, he made a 10 mile journey to Telford, and then took the branch coach for £3 to stand on the Stretford End. Those years, with their cracked terraces, cheap entry, and raw tribal atmosphere, remain etched in his memory as the most formative of his United journey.

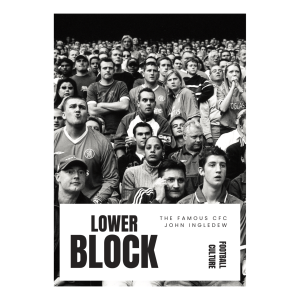

From hiding from Chelsea fans after a midweek draw, to being swept up in the Stretford End’s relentless roar during a League Cup semi-final against Middlesbrough in 1992, Duncan experienced the highs and edge of football culture before all-seater stadiums changed everything. He has since witnessed the transformation of Old Trafford into a polished Premier League venue, to a giant relic again in need of modernisation, losing much of its old character along the way.

Today, as a contributor to the long-running Red News fanzine, Duncan has found new meaning in selling copies outside the ground with his son. His story is one of changing times, but enduring love for Manchester United.

“Football reflects society, and Old Trafford, like other Premier League grounds, became a soulless Starbucks.”

“My family hails from the Rossendale valleys, about 15 miles north of Manchester. They were more interested in fine dining and showjumping, but back in the mid-80s I would occasionally go to Old Trafford with mates for birthday treats, usually low-key games against the likes of Oxford United or Southampton. Then, aged 11, we moved “south” to Bridgnorth in Shropshire, where I met a couple of lads my age who supported United. That’s when the obsession really kicked in.

Neither of them had ever been to Old Trafford, but I remembered ringing the United Club Call 0898 number to figure out how to get membership, tickets, and so on. That’s how I found out there was a supporters’ branch in Telford, about 10 miles away. At 13 or 14 years old, we’d make the 180-mile round trip, paying £3 for the coach and £3 at the gate to stand on the “Left Side” of the Stretford End. Those years between 1989 and 1993 remain the best of my United-supporting life.

-

Going to the Match | Richard Davis£8.50

Going to the Match | Richard Davis£8.50 -

Old Trafford Puddle£75.00 – £125.00Price range: £75.00 through £125.00

Old Trafford Puddle£75.00 – £125.00Price range: £75.00 through £125.00 -

MUFC Rotterdam 91 | Richard Davis£8.50

MUFC Rotterdam 91 | Richard Davis£8.50

The game still had a tribal edge, but Italia ’90 added a bit of post-Hillsborough glamour. Terracing made it cheap enough for teenagers, and the team was good enough to give you hope, but not so good that expectation weighed you down. I still remember the moment my two mates first stepped out from the tunnel to see Old Trafford. “It’s tiny! Looks much bigger on the telly!” Pre-kickoff, we couldn’t understand why the slightly older lads on the branch preferred the K-Stand seats or United Road Paddock, above and beside the away end in the Scoreboard End, instead of joining us on the Stretford End.

“We rarely discussed the match after the game. Instead, the songs or abuse towards the opposition players or away fans were as bigger part of matchday than Robson or Hughes were.”

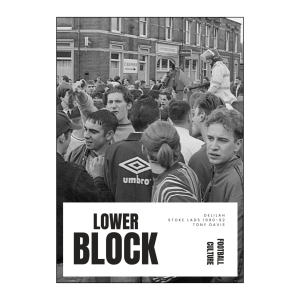

My abiding memory of that time is that we rarely discussed the match afterward. The songs, the abuse aimed at opposition players or away fans, were just as big a part of matchday as Robson or Hughes. I remember chanting anti-Chelsea ditties as we walked down Chester Road after a 1–1 midweek draw in 1991, only for the traffic lights to change and several cars of Chelsea fans pile out. Surrounded by lads twice our age, we hid behind billboards near the Railway Club until the lights turned green and they drove off. Like other kids our age, we’d also hang around by the old souvenir shop near the away end and watch United’s mob wait for the gates to open, knowing we were safe. It was part of the ritual. I remember a Liverpool fan swinging a car exhaust and shouting “Come Ed!” We were in hysterics, because it sounded like the Harry Enfield sketch on TV at the time.

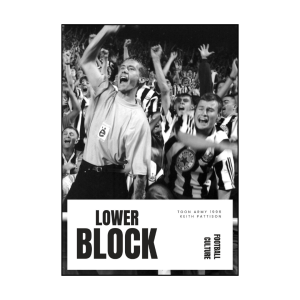

Best away fans? Possibly Dortmund in 1997, or for a few minutes before kickoff, 8,000 Stoke City supporters belting out “Delilah” in 1993. When asked my favourite match, people are always surprised it’s not a big European night but Middlesbrough in the League Cup semi-final in 1992. Boro brought thousands, filling the K-Stand and Scoreboard terrace. They fired rockets across the pitch and sang “You’ll Never Walk Alone” at half-time. The Stretford End, and then the whole ground, responded by singing “Ferguson’s Red and White Army” non-stop. The Stretford End pogoed up and down, physically shaking before a pitch invasion at the final whistle. A few months later it was gone. The wrecking balls came in, the terraces replaced by seats. By the third game of the all-seater 92/93 season, my mates vowed never to return, saying “it’s no longer the same.” For the next year I attended alone, before falling in with older lads and travelling home, away, and across Europe for the next 20 years.

“Each piece of silverware came at a cost. Every new season brought more “day-trippers” with souvenir bags, hammering another nail into matchday culture’s coffin.”

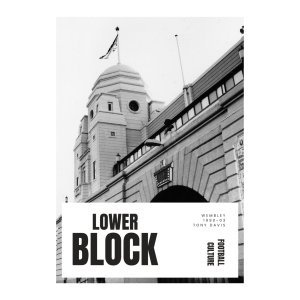

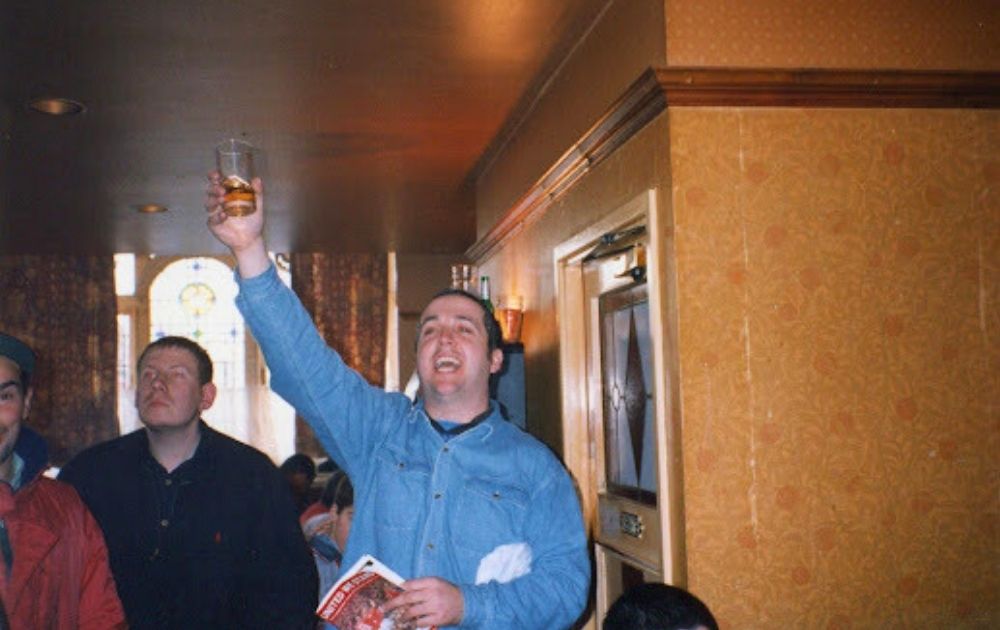

I’ve got plenty of memories of goals and trophies from the 1990s, but each piece of silverware came at a cost. After Euro ’96 every new season brought more “day-trippers” with souvenir bags, hammering another nail into matchday culture’s coffin, Old Trafford physically changed beyond recognition. Gone were the cracked, piss-stained terraces and even the bush growing from the Stretford End’s guttering. In their place rose glass fronts, cantilevers, and polish. Football reflects society, and Old Trafford, like other Premier League grounds, became a soulless Starbucks. By 2010 I’d had enough and handed back my season ticket. But in 2017, I began attending again with my five-year-old son. Over the last few seasons, I’ve arrived two hours before kickoff to stand on Sir Matt Busby Way selling the Red News fanzine.

“With so few kids at Premier League games in the last 30 years, songs are now learnt online rather than passed down organically.“

Attending as a parent and selling the fanzine has reinvigorated my matchday. Selling is a great way to people-watch and reflect on the variety of our support. Moments like sharing the Lyon game with my son are equal to Barcelona ’99 – his moments as much as mine. The Old Trafford crowd has become more international, with tourists arriving early asking “is that the programme?” before the regulars show up half an hour before kickoff. We sell 90% of the fanzines then. Still, thousands of working-class lads aged 20–30 walk past every other week. Yet the songbook, like that of other clubs, has declined in variety and quality. Every away end looks and sounds the same. With so few kids at Premier League games in the last 30 years, songs are now learnt online rather than passed down organically. Inside the ground there’s no fan configuration. People sit wherever they can get a ticket, not with like-minded mates. Half-and-half scarf wearers would never have lasted in the 1989 K-Stand.

Now, as my son turns 14 and talks about going with mates like I once did, I don’t know how my matchday experience will evolve. Maybe I’ll go back to watching with friends. Or maybe, if Sir Jim replaces Old Trafford with a “giant tent” and introduces real-time demand pricing, I’ll knock it on the head altogether. For now, I accept it isn’t what it used to be, but I still enjoy those pre-match hours standing among the terrace houses I’ve known since my teens – before the choice to attend is no longer mine.”

You may also enjoy…